REX REED IS ALIVE AND WELL

A premature obit for the prolific critic

Rex Reed is alive and well and living at the Dakota, the oldest surviving luxury apartment block in New York, and the spot where John Lennon was shot.

At 87 years old, Reed continues to contribute film reviews to the New York Observer, a regular occurrence since its launch in 1987. He remains at the 8th floor apartment he bought in 1969 for $30,000, refusing to sell to the highest bidder, even when it’s Andrew Lloyd Webber offering a hefty $8 million. The year Reed moved to the building on New York’s West 72nd Street he made his film debut as a leading man in Myra Breckinridge, an adaptation of the Gore Vidal novel, published the previous year. Reed was cast as Myron, a pre-op transexual, with Raquel Welch taking it from there as the post-op Myra (‘whom no man will ever possess’). Farrah Fawcett Majors features at the start of her career, with a bewildered Mae West, way beyond what should have been the end of hers. The author, the director and the cast disowned the film, with Rex Reed joining fellow critics in panning the project on its release. One review dismissed it as ‘an insult to intelligence, an affront to sensibility and an abomination to the eye’. Of his calamitous experience on set, Reed recalled: ‘Mae West spoke to no one but God, Raquel spoke only to the head of the studio, the head of the studio spoke only to God, who then related the message back to Mae West’.

For Reed, the acting credits that followed were few, and include a cameo as himself in Superman (1978), and a part in the Patrick Hamilton stage play Rope. He briefly returned to the stage in 2020, performing songs from the great American songbook in a cabaret show (‘Famous People I Have Known And The Songs They Sang’) that brought him across the lake to, oddly, the stage at The Pheasantry restaurant on London’s King’s Road. Prior to the making of Myra Breckinridge, Rex Reed was rightfully more familiar as a prolific, high profile writer of celebrity interviews. His byline appeared in key New York publications with the city’s name on the masthead - save for the The New Yorker. One of his few regrets.

A number of those early pieces were collected in his first book Do You Sleep In The Nude? (1968). The title is a reference to a question he asked actress Ava Gardner during the interview that established his name, his style, his skill at extracting a story from an interview, and squeezing words from a subject worthy of the dialogue for a role. ‘I knew everything all of those people had been in, every role they had ever played,’ he said, when commenting on his tactics, ‘and that impressed artists so much that they gave me a lot of information they would not have otherwise given a journalist’.

That interview introduced his name to the ‘new journalism’ canon, and landed in the 1973 anthology edited by leader of the pack, Tom Wolfe. This new genre brought the staples of fiction to non-fiction, such as scene setting, descriptive passages, and even plot. Wolfe credited Reed with raising the celebrity interview to a new level ‘through his frankness and his eye for social detail’. Yet, it’s another purveyor of the art Reed cited as a major influence - Gay Talese, whose ‘Frank Sinatra Has A Cold’ from 1966, is generally regarded as the greatest celebrity profile ever written. As with Reed’s take on Ava Gardner the following year - a former wife of Sinatra - it was published in Esquire. Talese made a point of examining his subjects outside their natural habitat. He was forensic on detail. A similar take is evident in Reed’s account of his afternoon with Ava Gardner:

She stands there, without benefit of a filter lens, against a room melting under the heat of lemony sofas and lavender walls and cream-and-peppermint-striped movie-star chairs, lost in the middle of that gilt-edge birthday-cake hotel of cupids and cupolas called The Regency. There is no script. No Minnelli to adjust the CinemaScope lens. Ice-blue rain beats against the windows and peppers Park Avenue below as Ava Gardner stalks her pink malted-milk cage like an elegant cheetah.

The actress is overbearing throughout, she overacts throughout, putting on a performance in which she dismisses her career and disregards former husbands, while using a drinking straw to alternate between a champagne glass brimming with Dom Perignon and another filled with cognac. The affectation, the lines delivered for dramatic effect, evoke the camp of a tragic Tennessee Williams heroine. Reed compares her to Alexandra Del Lago in Sweet Bird Of Youth. Gardner’s theatricality is a contrast to Reed’s technique when tackling an interview: ‘If I have any philosophy at all, it’s cancel the moon, turn off the klieg lights and tell the truth’.

Sometimes his interviewees surprised him. Barbra Streisand is one of the few he detested, after meeting her in the 1960s. David Bowie was a revelation in 1976: ‘I am amazed to discover that David Bowie is astoundingly literate, fantastically well-read, creative and professional. He has written nine screenplays, a book of poems and essays, a novel, and a collection of short stories. He’s into mysticism and numerology, and he’s very knowledgeable about everything in movies before 1933’.

Along with Gay Talese, still with us at 93, Rex Reed is the remaining survivor of the new journalism era. He’s the last of a generation of writers to interview the last Hollywood greats from the golden age that enthralled him from when he saw his first film - Gone With The Wind - as an infant. He’s the last of the small band of critics - both feared and revered - credited with transforming film criticism into an art form.

Pauline Kael of The New Yorker was the queen bee. She sat among Reed and his cohorts in the darkened hive of Manhattan picture houses, where the silence was broken by the dialogue on screen, and the sighs or gasps from Kael in response to it. Reed moved into the limelight, as a regular on Dick Cavett’s talk show, as a panellist on The Gong Show. Time magazine reported that he fielded 20 invitations to star-studded parties in one week. In 1968, Newsweek called him ‘the hottest byline around’. He still attends meetings at New York Film Critics Circle but is scathing, on page and screen, about the state of film criticism, an ‘irrelevant’ profession. Of modern critics, he says: ‘They have no swagger, no stature, no impact. Worst of all, they aren’t any fun. They don’t have feuds, in print or in person, and their quips (if they have any) don’t sting’.

Reed delivered quips that stung, something he had in common with another figure associated with the new journalism, but prominent as a novelist and a master of the celebrity interview - Truman Capote. Like Capote, Reed was raised in the American south, and made his way to New York with similar ambitions (‘I wanted to go somewhere where people knew things and they served drinks with umbrellas in them’). He later recalled: ‘I’ve always been attracted to unusual people who have enormous talent, like Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote, two of the greatest southern writers’. Again, in common with Capote, he became a target to fellow writers because of his barbed comments, particularly in recent years, with many offended and oppressed by any criticism levelled at them.

According to Reed: ‘People attack me because they don’t like me. Not because of my work. They just attack me on general principles, and I’ve never done that. Mainly, what I’m negative about is the lack of quality. And I think we’re drowning in mediocrity. I grew up at a time when it was not mediocre, and now it is’. His assaults on films considered masterpieces in some quarters are objectionable to those that adhere to a woke agenda. Get Out (2017) was one of the worst films he has ever seen (‘I didn’t care if all the black men are turned into robots’). Reviewing Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2003), he asks : ‘What else can you expect from a nation weaned on kimchi, a mixture of raw garlic and cabbage buried underground until it rots, dug up from the grave and then served in earthenware pots sold at the Seoul airport as souvenirs?’ In the ancient past he was called out for comparing Nancy Sinatra to a pizza waitress. In 2013, he was pilloried for describing Melissa McCarthy as ‘a female hippo’. One of his challengers wrote: ‘He is not the worst movie reviewer on the planet, merely the worst among the prominent’. His editor at the Observer, Merin Curotto, says of Reed: ‘He’s isn’t for everyone. Great talents usually aren’t’.

‘I’m 85 fucking years old,’ Rex Reed declared in Graydon Carter’s Air Mail magazine in 2024, with the theatricality of Ava Gardner stalking her lemony, lavendery, pepperminty room at The Regency hotel more than half a century earlier. ‘I’m tired of deadlines. I look forward to days when I don’t have to be anywhere’. The deadline he dreads is the one for which he doesn’t have a date. He’d rather not be discovered dead in a screening room, or slumped at his computer while reviewing a bad film. When withdrawing from the game, Pauline Kael noted: ‘You can take a lot of bad movies when you’re younger, but when you’re older you wonder why you’re doing it to yourself’. The films Reed can no longer stomach touch on themes he detests as much as he detested Barbara Streisand: fantasy, Sci-Fi and horror. In 2024, he said: ‘There are things I haven’t done in my life that I want to do, and they’re more important than writing movie reviews. I’m just so tired of writing’. Despite these protestations, he reminds us that readers ‘still want the Rex Reed byline’.

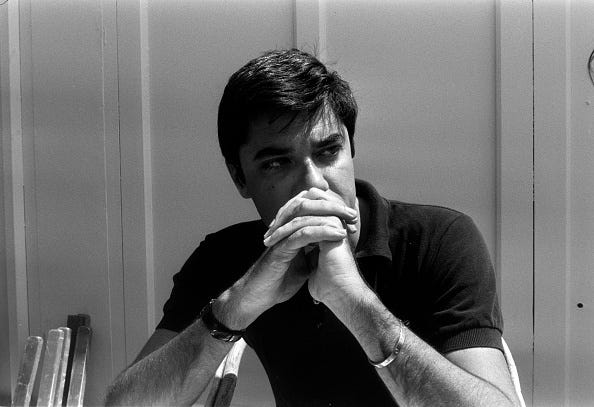

Reed’s been engaged in producing copy throughout his adult life. It’s akin to an agreeable two-way relationship, a marriage, without the sex or the shouting: ‘I don’t have ‘relationships,’ except friends. Love is not something that I’ve been really good at’. Warming to this theme in an interview in 2018, he concludes: ‘I think it’s all over as far as that goes. How do you start looking for a wife or a boyfriend or a significant other? It’s too late’. To paraphrase Reed, he’s now ’87 fucking years old’ and no longer the lean figure with the raven hair, cheekbones and eyebrows that belonged on Elvis, circa 1968. Neither is he the dandified talk show guest accessorising houndstooth jackets and Argyle suits - ‘a little Bill Blass’ number, he confided to a Dick Cavett audience - with cravats and ascots. It’s too late. Or was it never meant to be? Maybe Rex Reed, like Myra Breckinridge, is someone who no man will ever possess. ‘It would be nice, though,’ he concedes, ‘to find somebody who’s really handy with a wheelchair, because that day is coming’. In a profile for the Observer in 2024, Curotto wrote, with poignancy and insight: ‘His reflections on film, fame and what it means to leave a lasting impact show both the vulnerability of a man contemplating his legacy and the defiance of a critic who wants to set the terms of his exit’.

Rex Reed died on September 2, 2025. AI gently broke it to me, when I turned to Google to gauge if Reed was still with us, with a view to writing about his career. It very quickly transpired this was a 93-year old namesake from Savannah. An easy mistake to make. As AI explained: ‘Confusion regarding the critic’s status often stems from his long-running Observer column where he writes annual “In Memoriam” tributes to stars who have passed away, which can sometimes appear in search results alongside his name’. Had it been true the death would have been no surprise, as Reed is 87 fucking years of age. But I would have been shocked at the absence of obituaries alerting me to the news. Nothing from those New York magazines he contributed to, including Vogue and Esquire. No sightings in British broadsheets. Surely, on these shores he’s demise warranted a mention, for all those words, those interviews, those reviews, the books, the major flop he appeared in alongside Mae West and Raquel Welch. Or simply for his closing rendition of ‘I Was Lost, I Was Drifting’ on a spitefully cold March night at The Pheasantry restaurant on London’s King’s Road, as an audience of foreign tourists, and a gaggle of gay men old enough to have walked out of Myra Breckinridge, applauded.

Reed once referred to the libraries at newspapers as ‘the morgues’, where names like his were fading on ‘the yellowing pages’ from the past - first the bylines, then the obituaries. Those compiling obituaries in the 1960s prepared them early, in a decade when prominent figures went before their time. Presidents, pastors, pop stars, pop artists were taken out by an assassin, or survived an assassin’s bullet. Others were slaughtered by hippies in a luxury Hollywood residence. At that time, when Reed appeared on the Dick Cavett show, decked out in the ‘little Bill Blass number’ the host joked: ‘Oh, you’re older than I am’. Reed responded: ‘I think I’m older than everybody’. It was 1968. He was 30 years of age.

It was the year before his move to the Dakota. Cinema goers were given a glimpse into the grim yet stately interior in Roman Polanski’s gothic horror Rosemary’s Baby (1968). In August 1969, the director was in London, when his pregnant wife Sharon Tate and her guests were mutilated in the multiple murders at the couple’s Hollywood home, by members of the Manson ‘family’. Tate had come to prominence in the film adaptation of Jacqueline Susann’s best-selling novel, The Valley Of The Dolls. The author was one of the many people - if all is to be believed - invited to dinner at the Polanski home the evening of the tragedy. Susann sent her regrets after Rex Reed declined to be her date: ‘I said, “Jackie, I want to stay home and eat lemon meringue pie in my pyjamas, in front of the TV at the Beverly Hills Hotel”.’

The Tate murder changed Hollywood. Its celebrity inhabitants reinforced their security in efforts to guard themselves and their privacy. The assassination of John Lennon in 1980 had a similar impact on famous residents at the Dakota, where the Ono Lennon couple occupied an apartment or five from 1973. Rex Reed once gave his name to a petition to prevent the former Beatle being deported because of drug use and political activism. Lennon rewarded him with a one-year subscription to TV Guide. On the night of December 8, 1980, after shots rang out, Reed’s neighbour dispatched him to investigate and report back. Outside the building he found Lennon sprawled across the pavement with a stream of blood rippling towards the road. Reed helped get him into the police car that rushed him to Roosevelt Hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.

In the wake of the murder, the Dakota co-operative made fervent efforts to keep out high-profile figures making applications - such as Madonna - to avoid further notoriety. The monolithic building became less a sanctuary symbolising prestige and more a mausoleum tainted by Polanski’s film, which evoked memories of Sharon Tate’s murder, and the assassination of John Lennon. Somehow the sandstone facade, the dormers, spandrels, balustrades, gables, garrets, wood panelling, terracotta detailing and marble wainscotting is in keeping with this image, placing it at odds with other iconic buildings in the city designed by the same architect: the Plaza, the Waldorf Astoria.

The moment Rex Reed arrived there was the moment he truly arrived in New York, even though he’d moved to the city a decade earlier, existing on sandwiches from Woolworth’s, living in a one-room, roach-infested apartment - Aren’t they always in a writer’s story? - above a Chinese restaurant. At the Dakota his neighbour was Boris Karloff. Rudolph Nureyev and Lauren Bacall were residents. Reed arrived with a sleeping bag and a shopping cart stacked with books and records. In recent decades, death has diminished the celebrity quotient. Bigwigs in the banking industry have replaced them. The famous figures once found at the Dakota are within the line-up of photographs at the Rex Reed apartment. Among them, Angela Lansbury - who relocated her family to Ireland from Hollywood after the Tate murders - a long term friend of the critic.

When recalling his time as a student studying journalism in Louisiana, Reed said: ‘The first thing they taught everybody was the five W’s—who, what, why, when and where—that have to go into the opening paragraph. I hated that. I started stories about the color of the wallpaper’. This was in keeping with the ‘social details’ Tom Wolfe referred to when crediting Reed with elevating the status of the celebrity profile. You wonder if the writers turning up at the Dakota to interview Reed in his dotage are aware they owe him a debt. The profiles invariably begin with the ‘deep hunter green’ walls, before listing the abundance of antiques and the gallery of famous figures in photographs where Reed is the sole survivor in the frame. Some cast him, cruelly and predictably, as a Norma Desmond-type, whining that the pictures got small not the critics. All of which is wide of the mark. The critic became less relevant because the internet enabled everyone to become one via blogs, social media posts, and podcasts. To purists this demeaned the art of criticism, and is used as a slur when attacking veterans of the trade: ‘Rex Reed does not quite scrape the bottom of the barrel, not since the creation of the internet, at least’.

Reed is not averse to the positives of the digital age. The Observer became an online only magazine a decade ago, and certain Netflix projects have appeared favourably in his reviews. The Ripley series, based on the Patricia Highsmith novels, was ‘absolutely terrific’. From 2026, the Oscars will be broadcast on YouTube, in a move to make the ailing annual ceremony relevant in an age that’s already left it behind. ‘They have to stop thinking of new ways to improve the Oscars,’ Reed said. ‘Just show them and get them off the air.’ One year, after witnessing the ‘In Memoriam’ segment on the televised ceremony, he reacted with: ‘Those stupid dancers dancing around those tiny pictures of the people who died. You couldn’t tell who died!’

When the current Rex Reed goes the way of all flesh, and his namesake in Savannah, will he figure in this segment? Rather than wait, I set out to assemble a profile, a premature obit even. I was familiar with much of his output and some of his story, a little of which I garnered from a brief conversation we had at the end of the last century.

I was contracted as a development producer for a company based at Granada TV in Manchester. While working on an arts documentary treatment for a film on Jacqueline Susann that, ultimately, failed to come to fruition, I spoke with two prospective interviewees based in New York. The first was a rude, cranky close friend of the late author who’s name I’ve forgotten but who is forever planted in my memory as ‘the oldest, angriest, living lesbian in Manhattan’. The other was accommodating and courteous during the course of our transatlantic telephone call: Rex Reed.

He spoke to me from his Dakota apartment, looking out on West 72nd Street towards Central Park, and the Strawberry Fields memorial to John Lennon. My view, from a tiny office in a warehouse annexe at the TV studios, was of an empty Coronation Street set on a bleak Weatherfield afternoon. After thanking him for his time and before our “goodbyes” I mentioned that Myra Breckinridge was not the unmitigated failure so many had written it off as. It was part of the quirky, campy, alternative film canon from the beginning of the 1970s that included John Waters projects with Divine, and Warhol movies featuring The Factory ‘girls’ immortalised in Lou’ Reed’s ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ - Candy, Holly, Jackie. (Candy Darling pursued the Myra Breckinridge role, claiming it to be ‘her’ life story.) All of which seems quaint and archaic this century, now the LGBTQIA lobby has morphed from a minor movement into a mainstream cult, bringing unnecessary allies and an alphabet with it. ‘Oh, you really don’t have to say that!’ Rex Reed replied before signing off. But I meant it.

In the intervening years I occasionally returned to his books (Conversations In The Raw, People Are Crazy Here, among them), only once becoming aware of his adventures, when a minor headline emerged on the internet some time after the event it covered in 2000. Reed had been arrested for shoplifting, having left Tower Records on Broadway with CDs concealed about his person. What struck me was the forensic mention of the titles, as though central to the motive: Mel Torme’s California Suite, Peggy Lee Songs from Pete, and Carmen McRae’s Easy to Love (I was disappointed it wasn’t Bittersweet with her seminal rendition of ‘Ghost Of Yesterday’). Lee was so impressed that Reed was such a fan she reputedly sent him a CD box set of her back catalogue. He was charged with petty larceny and criminal possession of stolen property, while attributing the misdemeanour to a ‘senior moment’. Something his detractors have accused him of following inaccuracies and factual errors in reviews, as well as reportedly falling asleep during a screening, only to confuse his dream with the plot of the film.

The crime was not mentioned in the details provided to me by AI. The Ava Gardner interview was. There was a reference to his father being a drilling supervisor on oil rigs, which led to an itinerant childhood. In the introduction to Do You Sleep In The Nude? Reed recalls: ‘We lived in everything from a motel near a Tabasco sauce factory to a crumbling Southern mansion near Natchez — anywhere there was an oil boom’. Further AI facts appeared to be wrong, and were perhaps applicable to our man in Savannah. Thereby proving that even though AI is not human it is fallible, and too young to attribute its mistakes to a senior moment. One thing was certain. The Rex Taylor Reed born in Fort Worth, Texas, 1938, was alive and well and living at the Dakota.

‘Rex Reed would be dead today if he’d accepted the invitation to Sharon Tate’s doomed party,’ wrote the author John Lahr (son of the actor Bert Lahr, the lion in The Wizard Of Oz), in his New York Times review of Reed’s second book Valentines & Vitriol (1977). ‘Instead, he scavenges the bones thrown to him by the rich and famous.’ Here was an example of those critics that attack Reed himself, rather than critique the work. He, meanwhile, has his own take on his legacy, long after he escaped the fate of those murdered by the Manson gang at the house on Cielo Drive, while Reed was a short car ride away at The Beverly Hilton on Wilshire Boulevard. ‘I’m sorry I didn’t pursue the path of fiction,’ Reed has stated. ‘I do think I took the lowest form of journalism—which is celebrity interviews—and I did something with it. I think I elevated the genre in the pages of the New York Times and Esquire and New York magazine’. That will be his legacy, but what line will he pursue when THE END, the words that appeared at the close of the many films that preoccupied him from infancy, finally comes? It’s likely he will not go gently into that good night, and might take his cue from the ‘female’ heroine in the film in which he was cast as the male lead, Myra Breckinridge: ‘Let the dust take me when the adventure’s done and I shall make the dust glitter for all eternity with my marvellous fury’,