WHY WE NEED THE NERVE

A conversation with Maureen Callahan author of Ask Not

Maureen Callahan is a fervent advocate of the ten rules of writing as laid out by the novelist Elmore Leonard. She has adhered to these as a columnist, investigative journalist, author and, lately, presenter of the online podcast The Nerve.

It’s a few lines in and I’ve avoided breaking the first rule - never begin a piece of writing with a description of the weather. Now, I’m about to break the second: avoid prologues. The Nerve warrants a prologue, a fanfare even, it fulfils a crucial role at a key moment in the culture. Back in 2014, in her second book Champagne Supernovas, in which she writes on Alexander McQueen, Marc Jacobs and Kate Moss in an overview of the 1990s, Callahan mentions ‘a collective hunger for change’ following the excesses of the 1980s. This is equally true of the present. There’s a hunger for change.

I came to The Nerve shortly after its debut on YouTube in spring, and discovered that Callahan’s mission to take down those guilty of ‘befouling the culture’ was something I’d been longing to see. By way of a central monologue she forensically examines the behaviour, the words, the vanity projects of sacred cows such as Michelle Obama and Oprah Winfrey, while taking potshots at familiar targets that deserve the pile on. The hit list includes self-entitled celebrities, race grifters, self-help hucksters and nepo babies. Meghan Markle is a ‘malignant narcissist’ while Winfrey is ‘the master of the dark arts’, Jennifer Anniston ‘harbours anger issues’, Ryan Reynolds is a ‘psychopath’.

The Nerve addressed the Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs trial and the silence that greeted it, from those fierce independent women at the vanguard of celebrity sisterhood with ‘that feminist’ Beyoncé leading the charge. Callahan cites the First Amendment when protecting her right to offend, when insulting her subjects or indulging in gossip. As a chaser, she adds what is fast becoming a catchphrase, funnier every time she delivers it: ‘just my opinion’. Whether writing for the page or the podcast Callahan isn’t simply a contrarian, neither is she concerned by those that attack her take on the culture: ‘I don’t want to know people who aren’t critical thinkers and who can’t roll around in original, bold, provocative thought.’

The Nerve arrives at an apposite moment in America, while resonating with developments in Britain. ‘There’s a real hunger for this stuff in the culture,’ she says. A sea change is occurring in the US from the top down, following Donald Trump’s return to the White House. Here in the UK it’s from the bottom up, flourishing online, aided by podcasts and citizen journalists. It’s a refreshing alternative to the narrative peddled by the mainstream media. Here, we live under a regime that threatens our free speech by way of the Online Safety Act, proposed blasphemy laws, and lengthy jail sentences for social media posts that don’t meet with official groupthink.

Key figures in America claim they are exasperated at watching Britain destroying itself from within. Vice President J.D.Vance addressed his fears for the eradication of free speech in this country earlier this year. Many online pundits in the UK welcome the intervention of Elon Musk on X, as he highlights concerns overlooked by regime journalists. The week before his assassination, it was bizarre but heartwarming to have Charlie Kirk post an image of a protest against illegal immigrants in the Lincolnshire town of Skegness, from his Turning Point USA HQ in Arizona, with the words: ‘Rise up, England!’

The Nerve ushers in the new order and shows the celebrities, causes, themes that represent the old one the door. As the host points out, the show doesn’t deal in politics but it does deal in facts. It delves into territory familiar to all of us, which is why the correspondence she shares on the show is dispatched from faithful ‘troublemakers’ across the globe. Those tuning in spring from various countries and are of various ages, including men of a similar vintage to myself, such as one Armando J. Cortés: ‘I am a 64-year old fully hetero man, fully into man’s stuff, but I can’t get enough of your show’.

For me, a 64-year old single man with a shoulder bag and a sibilant ‘S’ that arrived with the dentures in March, The Nerve taps into an emerging trend within ye olde World Wide Web. Online content has been dominated by partisan opinion, by argument, by the need for the short, sharp take. To fully erase the ailing legacy media it’s now expanding beyond politics and polemic to embrace all that culture covers; the function of mainstream media before it became bogged down by the dying trends of DEI and identity politics. In the absence of our own equivalent of The Nerve this US model will suffice when ridding the culture of rot. A hand reaches across the ocean. I’m gripped.

Again, in keeping with Elmo’s ethos I’ll avoid a description of the weather or even a portrait of a place, but I’m impelled to introduce a setting, a backdrop, that suggests a unique mood: New York. It’s where the three hour-long episodes of The Nerve are recorded each week. It’s where Maureen Callahan was born. ( Her Brooklyn-based parents soon relocated the family to the Long Island suburb of Long Beach.) It’s where she found the pop culture that formed her……where the New York titles she later contributed to informed her aspiration to become a writer. It’s the birthplace of Lady Gaga, the subject of her first book in 2010. Callahan’s reasons for writing Poker Face were twofold: firstly, to crack the task of writing a book, secondly, to buy a home with the proceeds, in New York City

A decade on Callahan has two high profile books under her belt on subjects far removed from those earlier titles. The award-winning American Predator (2020) is her forensic pursuit of the crimes of Israel Keyes (‘the first sui generis serial killer of the twenty-first century’). Last year’s New York Times bestseller, Ask Not, is an account of the women used and abused during their association with the Kennedy clan. She speaks to me from her house at the opulent end of Long Island, a serious drive from the middle class suburb of her formative years, and closer to the exclusive resort where Manhattan-based celebrities - the breed she targets on The Nerve - have holiday homes: The Hamptons.

Michael: The Nerve is the first outing for former NBC anchor Megyn Kelly, in expanding her burgeoning online media empire beyond The Megyn Kelly Show. Your appearance as a guest on Kelly’s podcast - including the two of you spoofing With love, Meghan and the space mission of Katy Perry and the celebrity female ‘astronauts’ - provided an enticing introduction to the monologues you now deliver on your show. This must have brought an audience to The Nerve early on.

Maureen: The reaction to the show from the beginning was so strong. Whenever you start something like this, they come at you with metrics and they say this is how we can predict what kind of audience you’re going to capture maybe in year one. After the first episode they were like The Nerve just blew past the year long predictions. So we knew we had, quote, unquote, struck a nerve. The name of the show is multilayered. And what’s extremely gratifying is that we are doing what we set out to do, which is be a singular voice. Nobody’s doing what we’re doing. Nobody is coming at pop. And I come at pop culture as a fan. But, we’re the really dark side of the moon. We’re the entertainment show that would be broadcast in Satan’s waiting room. At The Nerve we serve as a corrective in some ways, a fun, funny but brutal and honest corrective. We’re telling true stories.

Michael: You’ve walked a long way and covered a lot of ground on the way to this point. Did all roads lead here?

Maureen: I feel like everything I’ve done in my career before has prepared me for this. I think it’s kind of why the show has taken off in a way, because we know exactly what we’re doing. When I criticise a subject who is otherwise getting glad handed in the American media, I go back and look at everything they’ve written. I look at interviews. I like to use their own words, their own statements, their own actions, their own contradictions to build my argument as to why I may think the way I do, because I do present so much of it as my opinion. I’m protected. I have a backlog of factual data that I am presenting and saying.

Michael: Your skills as an investigative journalist come into play on The Nerve, and you have more freedom in America to go on the attack, which is increasingly impossible in Britain. Stating your views as your own opinion allows you the freedom to call Ryan Reynolds a ‘psychopath’.

Maureen: I think he is a psychopath. I think he is a dead eyed psychopath whose smile never reaches his eyes, who has a lot of dark stuff in his past. The thing that’s remarkable about so many of these celebrities who are elevated to untouchable status is it’s like a cultural caste system over here. They often tell us who they are in plain sight. They may do it behind a laugh and a wink and a nod, but they often tell us the truth about who they are. Right now, here in America, we’re watching Priscilla Presley (ex-wife of Elvis) do a media tour. Now the number one question is, Priscilla, you’re being sued because your former business partners allege that you pulled the plug on your daughter prematurely so you could wrest control of Graceland from her. What’s the story? She doesn’t get asked that question. She gets a little bit of tiptoeing around it and it’s really unpleasant. So let’s not touch it. You’re a nice old lady. I don’t think she’s a nice old lady. I think she’s a dark, malevolent force.

Same thing with Amy Griffin, the wife of this billionaire here in America who has been peddling a memoir - The Tell - that was swallowed whole by the media industrial complex, by the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Gwyneth Paltrow. In this book, she alleges that a teacher who she keeps pseudonymous, but who is a real man and everyone in her city of Amarillo knows exactly who this guy is, raped her repeatedly as a child, multiple times in public places, and nobody saw a thing. And we at The Nerve were the first to do a segment. And I was very, very careful about this because you never want to take a claim of sexual violence lightly, and I don’t. But Griffin’s book read way off to me. I didn’t believe it. So we did a little bit of digging, we went to Amy Griffin’s people, we emailed a list of questions. One of those questions was - If there is a violent child sexual predator on the loose, do you not feel any responsibility to make sure this person can never harm another child? Because child sexual predators never stop at one. And we heard crickets. So the New York Times picked up this thread and just ran an exposé. Her lawyers got back to the Times. They didn’t even come back to us. Now maybe they didn’t come back to us because they thought, oh, this cute little podcast, who’s gonna listen? But that’s great for us. Underestimate us at your peril.

Michael: I like the way you highlight the hypocrisy of celebrities when they fall silent on certain subjects, while questioning why we should listen to their opinions anyway.

Maureen: Yes, the notion that they have to opine about everything no matter what it is, whether it’s geopolitical, whether it’s a once in a century plague, whatever it is. We just covered Violet Affleck, the 19-year old daughter of Ben Affleck and Jennifer Garner. She goes over to the United Nations behind a mask and demands that the world mask up again because she needs to feel safe. Somehow, the culture did it to her. She’s a sick girl and as I’ve said, not for the reasons she thinks. She needs a lot of help. Just my opinion. But you know this girl is there by dint of her parents fame. This is a borrowed list of accomplishments that she is using to stand before the United Nations and make a nonsensical argument and demand. This is the outgrowth of everything the culture has allowed thus far.

Michael: I believe the couple also have a transgender child, a trend that’s almost as evident as nepotism among the Hollywood elite.

Maureen: We covered this earlier on The Nerve, and yes, it’s disproportionate. Because if you were to do a one to one with the segment of the population that is truly trans, it’s a very tiny, infinitesimal percentage. If you were to do a one to one of the Hollywood community or the celebrity community, and the number of those people who have one child, if not all of their children are trans or on the spectrum or on some sort of sexuality or gender spectrum, mathematically it’s statistically impossible. I interpret it two ways. One is, these children are often born to malignant narcissists, and they’ve got to do something to get attention in that house. And if that’s what it takes, that’s what it takes. Or secondly, it’s encouraged by parents who are social justice warriors and virtue signallers. It redounds to their own cultural halo of importance and righteousness.

Michael: A cast of characters have become targets on The Nerve. One of these ‘repeat offenders’ as you refer to them, is Sarah Jessica Parker. You have this knack of moving in on figures that I’ve felt are deserving of criticism. Parker is one such target, as the character of Carrie Bradshaw which she exhausted in the Sex And The City brand and finally buried with the lamentable And Just Like That. An event which you rightly celebrated by way of a funeral on The Nerve. For me, Sex And The City took some risks and brought fashion and a modernity to comedy and drama in the 1990s, but the Parker character was the weakest link. She’s now the Methuselah of Manhattan. The older she got the more infantilised her wardrobe became, along with her behaviour, as though this was short-hand for being ageless and sexy: the elongated knitted sleeves covering the knuckles, wearing the boyfriend’s oversized shirt the morning after sex. The injection of woke and desperate shock tactics into And Just Like That made it a prime target for The Nerve. I take it that even though you were walking similar streets in the 1990s, experiencing similar events, the New York of Carrie Bradshaw was not for you, then or now.

Maureen: I hate watched Sex in the City. I could appreciate the aspirational qualities of it. But I knew way too many young women who moved to Manhattan thinking that was the life that they were going to have and identified as, everybody’s a Carrie Bradshaw. It’s like how everyone who believes in reincarnation believes they used to be a queen, you know, I’m a Carrie. They’re never a slave or a foot soldier or a janitor. New York for me was downtown. As a teenager, I worked as an intern at MTV. That’s when it was small enough and nimble enough you could soak up everything about television production and how that worked. That was such a great time to be a young person in New York in the 90s and the early noughties. You still had an underground here. The internet has really erased that. I’m sure you relate to this. You sort of had to earn your bona fides if you were interested in subcultures. You really had to listen and think and absorb and chase these things down. They weren’t just a Google search away. It was the way that people really identified. Everybody had tribes. So the girls with the nameplates and the $14 mimosas, that was not my scene. That was not for me. I was into young Cool Britannia. Kate Moss, Trainspotting, Blur versus Pulp. All of it.

Michael: Yes, I can relate to so much of that. But I was a very late baby boomer, while you arrived by way of Gen X. I left infancy as glam rock (Bowie, Roxy Music) was colonising the British music charts, hit adolescence in time for punk, and became a fully-fledged adult with ‘new romanticism’ before the Eighties went full pelt. I was working in television at the same time as you, in the 1990s. I began as a researcher on Tonight With Jonathan Ross at Channel 4, his attempt to bring the David Letterman show to these parts. What was happening in television at that time was akin to what’s happening with the internet now in terms of a challenge to orthodox broadcasting. MTV was coming up on the outside, while in Britain you had a nascent Channel Four commissioning independent production companies to create ‘yoof’ TV, redefine breakfast television and the talk show. Ross was unique in that he introduced mainstream television to trends and content we previously had to seek out in the margins; searching for clues, putting in the legwork, when it came to music, clubs, film and fashion.

Maureen: That all speaks to me, all of that stuff you’re talking about.

Michael: In the 1970s it was a private code, rather like the ‘camp’ Susan Sontag defined a decade earlier. I was a Londoner, on the poor side of town, but a few tube stops from the action. Everything was done on the cheap, but that somehow made the experience more unique. If aspects of the wealthy west end felt like another country, despite its proximity, New York was another world, but one we looked to with awe, particularly the world of Warhol. I remember skipping school one Monday afternoon in February 1977 to head for King’s Road where I forked out for Andy Warhol’s Interview, the last issue with his name on the masthead. Even though you were part of the rising generation, the reference points you often allude to on The Nerve suggest the era before you came of age was your playground. You mention John Waters films, the New York of Warhol, The Factory, Studio 54.

Maureen: Oh, my God, I wish. When I was a kid, like a very young kid, I would go to the library and read New York magazine. From the time I was able to read, I was like reading the New York Post. So it’s like, oh, Andy Warhol’s Diaries are out. Go to the library, get Andy Warhol’s Diaries. The same with Studio 54. Watch the documentaries, talk to people who were there. The people in the margins are always the most interesting to me. Also because they’ve been through the most as young people to get to where they are and they see the world differently.

Michael: I agree that the arrival of the internet meant you didn’t have to put in the legwork to discover fellow travellers with a similar sensibility. All that was once in the margins has found its way to the heart of the mainstream, and with it has come the worst of everything. From the vantage point of the present there is something quaint about David Bowie playing gay for a day, and Lou Reed dating a transsexual. Even the Warhol Factory fodder cast as ‘superstars’ by the artist, appear endearing in their efforts to pay homage to old Hollywood starlets. And they did so despite the hard drugs and harsh drag that determined their lives, and the heroin addiction and hormone treatment that hurried their deaths along. In place of the anomalous transsexuals and transvestites that made us odd outsiders avert our eyes and prick up our ears, there is now a militant trans lobby which is treated as a protected species.

The prominence of drag in mainstream culture is part of a trend that embraces Susan Sontag’s take on Camp. But it also breaks with it. According to Sontag it was never political; it made the serious frivolous. Contemporary Camp makes the frivolous serious. It has lost its outsider status despite fervently clinging to it; it is no longer a subversive subculture. In 2013, filmmaker Bruce LaBruce wrote an essay in which he revised and updated Sontag’s original. He took her to task for arguing that Camp was apolitical, claiming that’s exactly what it was — until now, an age in which he sees “bad straight camp” and “conservative camp”. Several years on, bad Camp and fakery sum up what is dominant in the culture, particularly when it comes to political activism. The serious has become frivolous. The exaggeration, theatre and artifice of Camp coloured the antics of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and the supporting cast of agitators that take to the streets, whether it’s women dressing as extras from The Handmaid’s Tale or Black Lives Matter foot soldiers reprising Black Panther costumes.

In the aftermath of his death, George Floyd was inducted into the contemporary canon of bad Camp. Even before his canonisation his 14-karat gold-plated casket was displayed for the curious crowds as though he were Mandela or Evita. Drag and Camp are interchangeable because each derives from themes central to Sontag’s thesis: a love of the unnatural by way of artifice and exaggeration. Things being what they are not.

I recall a podcast interview following the launch of The Nerve, in which you said: ‘People have had it with the falsity and the bad art that would be camp, if it wasn’t so bad.’

Maureen: They are so fake now, the ones doing it. They fool you. Talking to you about this and listening to you talk, I so relate. I was in Catholic school, but I was that kid who on the weekends was on the train into the city and going to all of the independent record stores and all of the vintage shops, soaking up everything that was either counterculture or that came before me that was informing that decade. My humble hope would be that The Nerve is the place where everyone who thinks differently, feels differently, absorbs things on the margins, is questioning what the mainstream is telling us is true and real. I would like The Nerve to be the destination for everyone like that, because that’s definitely informing where I come from, I think. That’s why I get those children are the ones who grow up to be the most interesting and the biggest contributors to the culture because they see the world differently and they don’t care if you like it. They don’t care if the other kids like it. They’re not going to push themselves like a square peg into a round hole.

Michael: Speaking of mainstream media, there is a speech by Camille Paglia in the early days of this century in which she riffs on the decline of the ‘Manhattan media’, beginning with the Village Voice. Since then Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, The New York Times, New York magazine have followed suit, having been consumed by Trump Derangement Syndrome since 2016. It’s a long way from Dorothy Parker and her witty cohorts at The Algonquin Round Table writing for The New Yorker in the 1920s. Or the new journalism commissioned by Clay Felker, when he edited New York magazine in the 1960s, with Tom Wolfe heading the pack. All of which you are familiar with and fond of. These writers were iconoclasts unafraid of attacking and insulting the saintly and the sacred figures of the age. I believe The Nerve, with you at the helm, has a boldness and a spirit similar to this that’s absent in a climate reeling from censorship and cancel culture.

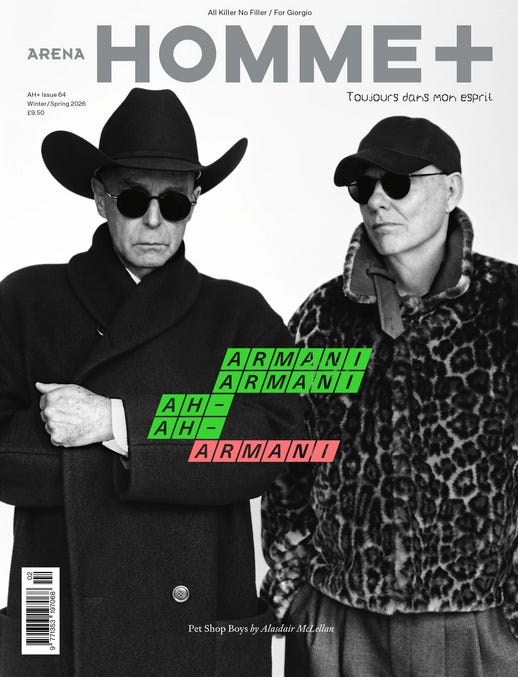

Maureen: I think there are so many factors. Trump is definitely one. We try to stay pretty apolitical at The Nerve because things are fractious on both sides. But in terms of the decline of media and magazines, and I grew up loving magazines and even now, like, there are still a few. I’ll go into a good New York magazine shop and I’ll buy smaller titles, anything that feels like it’s got a finger on a pulse of anything. But Vanity Fair is dead. It died the minute Graydon Carter left and Vanity Fair went woke. A lot of these publications went woke. They took the teeth out. You cannot criticise anybody anymore. And I feel like it is an outgrowth of wokeism to an extent, you know, because what if you’re insulting somebody who later says, hey, I’m marginalised over here - you, Michael, were talking about being marginalised to be a point of pride. Now everybody’s cloaked in victimhood. It’s so boring.

Michael: It astounds me that much of the fashion press can be so brilliantly attuned to contemporary cultural trends, and yet be stuck in another age when it comes to politics; flagging up tired student causes relating to battles that have largely been won, so as to expand the victimhood of ‘beleaguered’ minorities. Just my opinion. I like the way you straddle high end and low when it comes to your reading and research. You’ve fond memories of both Mad and true crime stories, you’re an ardent consumer of gossip and fashion magazines, but you appreciate the ‘shoe leather reporting’ of the National Enquirer. It all comes together on The Nerve, but equally in the columns you’ve contributed to the Daily Mail and the New York Post.

Maureen: It’s kind of why Andy Warhol was something of a spiritual godfather. That love of the high and the low and realising how fine that line can often be. Just one step in the other direction. I think that’s where this, the magic is and the secret sauce is. I’m sure you’ve encountered this too in your life where you meet people who you would think have far better things to occupy their minds than gossip. Everybody loves gossip. Everybody wants to know what this person over here is doing, or this vaunted idol over here, this celebrity. What’s the real story? What’s going on? You know, everybody loves it.

Michael: As a non-fiction author you’ve examined the psychology of a serial killer who famously had ‘no digital footprint, no paper trail’ in American Predator, you are therefore perfectly placed to tackle modern celebrity and unearth what lies beneath.

Maureen: I’m fascinated by psychology, by human psychology, by people who have the need such as a Meghan Markle to become that famous. You know, she’s got a black hole, she’s never going to fill. The fun of The Nerve is that selfishly I get to explore all of these topics and, and there’s a Venn diagram. I mean they all overlap. You know, there’s a lot of personality disorder when you look at people who thrust themselves that high on a platform, whether it’s an Oprah, whether it’s a Michelle Obama, you know, it’s politics, it’s pop culture, it’s everywhere. We do these deep dives into certain kinds of personality disorders, people to look out for, breaking apart all the different kinds of narcissism, breaking apart body language. Our tagline is ‘real talk about fake people’. We are always looking for the real story underneath. When I talk about Oprah Winfrey and I say I think she’s a dark force in the culture, people laugh sometimes. But I’m also being dead serious and I always lay out, as you said, as the author of a true crime book, the case for the audience. In my mind, I’m a cultural criminal prosecutor.

Michael: The Nerve also highlights figures that have elevated the culture rather than ‘befouled’ it, those from the past and present famous for kicking against the pricks. Some of them are sorely missed - Joan Rivers, Christopher Hitchens. Others remain with us, Ricky Gervais for one. Being a lover of language you also call out those committing the sin of befouling it, including Kamala Harris with her nonsensical word salads, and the platitudes that fall from the lips of Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey, Meghan Markle. But what dominates as a recurring theme when delving into the psyche of these celebrities is what you refer to as a ‘darkness’. A touch of Hollywood Babylon perhaps?

Maureen: There is a darkness there on so many levels. Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs trial is one of the darker events of the year. He was ultimately convicted on what were the lesser charges. I think the jury got that wrong. I think it’s very, very possible that someone from his camp got to at least one juror. We know he was trying to intimidate witnesses from behind bars. That’s why he was locked up before trial in the first place. All of these virtue signallers in Hollywood, women especially, who, in the wake of Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo, who went to the Oscars that year wearing black. We’re all mourning. We’re all in. You know, nobody stood up to him. Everybody enabled it, and they’re not even looking at themselves. Oprah gets up there at The Golden Globes and says she’s gonna make sure another woman in Hollywood never goes through this again. If I go to my grave having abolished Oprah Winfrey as the self-help guru of the age, I will die a happy woman.

Michael: There is a connection here with all that came into play with the establishment protecting the image of the Kennedys and more recently, the Bidens.

Maureen: Everybody went silent. We have seen the photos from the parties of all of the celebrities who were at the parties. The Ashton Kutchers, J-Lo, who was arrested with Combs back in the 90s, during a nightclub shooting, a woman was shot in the face. Jennifer Lopez gets to the police precinct and says, ‘go get me some cuticle cream’. These are the people that the culture still elevates, you know, and it’s remarkable to me. I couldn’t believe that everybody was getting away with not being asked. What do you think about the Diddy trial? Hey, you know him? What did you see? What do you know? The entire celebrity industrial complex, from the major magazines to the entertainment shows, to the famous podcasters like Oprah - we don’t touch that stuff. It was remarkable to me that Sean Combs has been the only person who has gone down for this stuff, because you cannot tell me that there are not major players who were at those parties participating in this abuse of women.

Michael: Let’s talk about womanhood, another suitable subject for you, someone who grew up reading books on female saints and First Ladies. In calling out the ‘repeat offenders’ in the culture on The Nerve you arrive at certain types such as ‘the malignant narcissist’, ‘the misogynistic gay man’, but equally there is a type of modern female celebrity unique to the age that comes under fire. She’s tanked up on empathy, hysterical on protests and marches, and yet surprisingly coldly casual when it comes to issues such as late-stage abortion. The woefully woke Cynthia Nixon, whose career will hopefully go the way of Just like That, is a pensionable example of this type. She parades her trans children, wears a Palestine flag blouse, sports a MAGA-style red baseball cap emblazoned with the words ‘Make Abortion Great Again’. The Nerve did a beautiful and brilliant take down of Nixon and her ilk in the segment ‘Celebrity Abortions’.

Maureen: I think even the most ardent pro choice among us can agree that abortion is a tragedy. You know that Lily Allen clip of her talking about her multiple abortions and how fun they were and how she can’t even remember how many she had? These are a kind of female celebrity that strike me as profoundly dumb and uneducated and who somehow think that it is the height of modern day feminism to celebrate multiple abortions as a win. Especially women who are wealthy and privileged, a Lily Allen or a Cynthia Nixon, who should know how to prevent an unwanted pregnancy in the first place. I feel as though we are at a particularly ghoulish time right now. I don’t know what forces are coalescing here, but again, The Nerve exists to expose these people and purge them.

Michael: Are there other examples of this ghoulish trend?

Maureen: We have another author here, a very famous one named Elizabeth Gilbert, a product of the Oprah industrial complex, propped up by her decades ago with the book Eat Pray Love, who is now hawking another book, a memoir. Her girlfriend is dying of cancer. They’ve gotten themselves on a great drug and alcohol binge. Liz has tired of taking care of this girlfriend who she otherwise has said is the love of her life. And so she, in the pages of this book, talks about plotting to murder her girlfriend, actively plotting to murder this woman and how she was going to swap out her chemo pills for medication, whether it was fentanyl or something else, I forget, and knock her unconscious. And then once she was unconscious, smother her to death with a pillow over her face. This is treated like a really cute anecdote. Oprah, in interviewing her was like - ‘Wow, things got really dark for you, right, Liz?’ Dark for you? Dark for this poor woman who’s already dying of cancer, who has a potential murderer pretending to be the person who loves her the most in this world. Liz sails through a lot of these interviews like she’s a genius. She positions herself as a self help guru. She throws retreats where she charges women thousands of dollars to spend weekends in her company.

Michael: Perhaps the most tragic recent event that epitomises the darkness within the culture, and the mindset that contributes to it, was the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Following on from the attempt on Donald Trump’s life, this brought back memories of the US in the 1960s - the assassination of two Kennedys, one King, and the bid by Valerie Solanas to take out Andy Warhol with a bullet. This must have resonated with you in particular, having re-visited the lives of the Kennedys when writing Ask Not.

Maureen: I feel like we’ve crossed a Rubicon. I thought a lot that day about what it must have been like to be an American in the 60s, where three leading lights were gunned down. JFK, MLK, RFK. I guess the closest parallel to Charlie would have been in MLK. He was a leader. He was a religious leader. He wasn’t a politician. I found that the symbolism of Charlie being shot in the throat is terrifying. And we now know that the gunman was waiting for Charlie to answer a question about the trans issue. And that’s when he chose to pull the trigger. He was waiting for it. I think this loops into what we were talking about earlier. I am gobsmacked by this culture of death that we are living through right now, This celebration of death and true mortification when Luigi Mangione is celebrated by the culture for assassinating a husband and father and is the subject of a musical in San Francisco. He has groupies. Going back to Diddy. They’re housed in the same facility in Brooklyn. Diddy’s very upset. You want to know why? Because Luigi gets more fan mail. I’m not making this up. You say, well, why? I think it’s because we’ve slowly and silently built to this. To this level of darkness in the culture, that’s the cost of whistling past the graveyard culturally. That’s the cost of letting a lot of these people off the hook or explaining away their misdeeds or their malfeasance. I think people have had enough of it.

Michael: I was watching The Megyn Kelly Show on YouTube when I received news, via email, that Charlie Kirk had been shot. The show was a recording from the day before. I quickly scanned X, then clicked on YouTube and Kelly’s live podcast. She was discussing the shooting with her guests, all of whom were naturally emotional as they knew Kirk personally, or knew of him and respected him. When she read out confirmation that he’d died it was the most intimate, personal experience to be privy to via this platform, watching her shattered by the news, and her stoicism in making it through the rest of the show as she reacted to the tragedy. At one point she said she didn’t know what she was waiting for, she was a figure behind a desk talking into a void, holding it together. To a viewer, it was so raw, so real, but equally an experience unique to the age, and the new media that now dominates.

Maureen: You know I said this to Megyn on her show the other day. When that news broke I was out. I got home, I turned on my TV. By which I mean I put YouTube on my TV and put her show on, because I knew out of anybody broadcasting she would be telling the story factually and truthfully and giving it every bit of investment that it deserved.

Michael: It struck me that this event also marked another nail in the coffin of legacy media, for whom Charlie Kirk’s death, at first, was a footnote, even an inconvenience.

Maureen: I agree with you, this new medium, there is an intimacy to it and you know, what’s missing from it really, as you just said, is artifice. It’s not the sets and the lights and the music and the producer. It’s not that. It’s a one to one discussion. We’re all experiencing this thing together. There’s no ‘I’m going to tell you how to feel about it’, which so much of legacy media is about. Right? It’s like, ‘Oh no, you don’t understand how to think and feel about this. We’re going to tell you’. Or we’re going to lie by omission. We’re going to leave things out. You know, first of all, number one, the New York Times the next day in their physical paper, not a single op ed about this. So two weeks later, front page, above the fold: ‘If only we knew what motivated Charlie Kirk’s killer. If only he had left some clues behind’. So if this is the only media that you are consuming because of bias, and wanting to have your views reinforced, then that’s really what you think is the truth.

Michael: The famous line about everyone knowing where they were when President Kennedy died feeds into this. Years from now, some of us will remember where we were when we heard Charlie Kirk had been shot. We were online, watching a live podcast, and reading the shocked reaction of those responding to the assassination on social media posts.

Maureen: You know that stuff is going to be replayed. What is replayed every anniversary of the JFK assassination is Walter Cronkite removing his glasses and tearing up, saying the President has been pronounced dead. That’s because that was a one on one with the viewer, with the fellow citizen. Even though it’s behind a screen, it felt unmediated. It felt authentic.

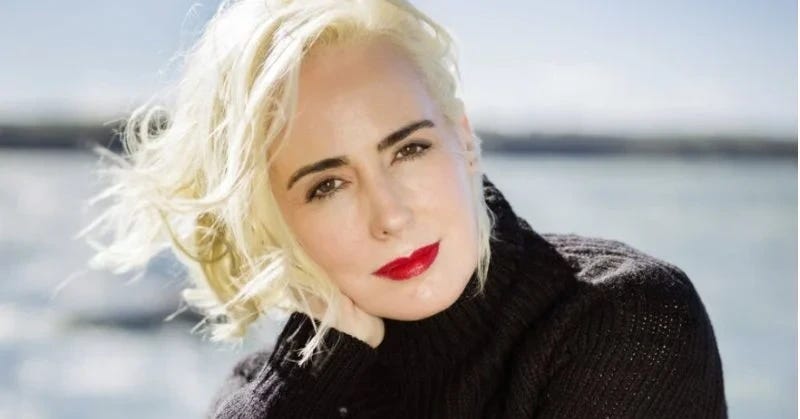

‘I like it when you get hysterical on The Nerve,’ I told Maureen Callahan before we finished a two hour conversation. ‘You look great on screen,’ I added, meaning both on The Nerve and during our Zoom hook up. Shoulder length platinum blonde hair, the occasional old school secretary spectacles that make you want to ask her to ‘take a letter’. Often a black sweater and pearls that bring to mind Audrey Hepburn (we discussed her, she’s a fan). Days after our conversation Maureen fronted The Nerve wearing a vintage Roxy Music t-shirt (we discussed them, we are fans) accessorised with two rows of pearls - a nod to the era when Roxy were in the charts and Warhol was on the town (we discussed this).

Other guests sometimes appear on screen, and The Nerve hosted a panel when it covered the Emmy Awards, but the host alone addressing the camera via a monologue is when it’s at its best - smart, wise, witty, articulate, turning up the heat, reaching fever pitch and heading towards hysterical. There’s a touch Camille Paglia about Maureen Callahan’s presentation…. a touch of Sandra Bernhard…..a touch of that spirit we discussed that once made the like-minded outliers among us seek each other out and assemble in the margins. This is not just an age thing. The rising generation on TikTok are railing against the outmoded culture of woke, identity politics, censorship and the ailing legacy media. They’re done with safe spaces and trigger warnings.

In September this year, Maureen Callahan wrote: ‘The bulk of Americans are tuning out of linear television and an infotainment complex that, under the banner of free speech, insisted, for years, that these baldfaced lies were true: The Hunter Biden laptop wasn’t real. Covid lockdowns were necessary. Donald Trump is Hitler. Joe Biden was in top mental and physical condition to run for a second term. That last whopper was the death knell for liberal corporate media…’ The celebrated American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, now long gone, believed the invention of television meant that for the first time ‘the young are seeing history made before it is censored by their elders’. Television no longer performs that role. The mainstream media has become the adult censoring history and treating viewers like children. The baton, the mantle, has been taken up by online podcasters, citizen journalists, and individual pundits of all ages stepping into the breach. The culture is at a turning point. If there’s a revolution going on, in the culture, in broadcasting, it’s a revolution that will not be televised.

I love this. I am a Troublemaker, a HUGE fan of Maureen’s incredible writing and of course, The Nerve.

Loved this piece. Between those discussions and the insights you share from your MTV days, it really clicked for me why I love this show so much. It gives me that warm, nostalgic feeling—taking me back to the 90s and early noughties, before social media flattened culture and authenticity became performative.

You manage to transport us back to a time when media felt sharper, funnier, and more honest—while also calling out the exact assholes who’ve made modern media so exhausting. It’s refreshing, cathartic, and genuinely entertaining in a way that feels rare now.

That’s why The Nerve works: it’s real in a world that’s become aggressively inauthentic.